A personal reflection BY HELEN CHERULLO

Twenty years have passed since I made the most consequential decision of my professional career: publishing Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Seasons of Life and Land with Subhankar Banerjee.

In 2003 just days after the book was printed, Senator Barbara Boxer held the book up on the floor of the United States Senate during debate on a bill to open the Refuge to drilling. Surrounded by photographs from the book, she said the images of life on the arctic coastal plain during all four seasons of the year and the indigenous people who live on the land refuted comments from other senators characterizing the land as a “blank white nothingness,” devoid of life. She offered an amendment against opening this American wildlife refuge to drilling.

When the votes were counted, the Arctic Refuge was saved from development by a narrow vote of 52 to 48. Subhankar and I dreamed of creating a work of art that would change the world. In that moment, we believed we had.

After the vote, the book and photographer Subhankar Banerjee were catapulted into the national media. Through unexpected philanthropic support from three extraordinary foundations—Lannan, Campion, and The Mountaineers—the images and stories from the book were leveraged into a national media campaign, over 50 multimedia events, six traveling museum exhibits, and partnerships with numerous grassroots groups working to preserve the Arctic Refuge. With donor support, over 10,000 books were donated to libraries around the country, and presented to media, influencers, and public policy makers.

Art for Advocacy

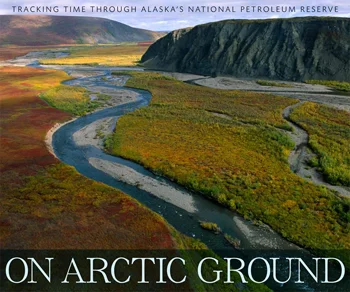

This revelation resulted in creating a dedicated nonprofit affiliated with Mountaineers Books: Braided River, committed to preserving the last wild and sacred lands in western North America. At Braided River, we work closely with our colleagues at Mountaineers Books, and with photographers, writers, artists, grassroots campaigns and philanthropic individuals, Indigenous communities and grassroots organizations to weave together images and prose that connect these wild and remote landscapes to a shared, viable, and equitable future.

Powerful Braided River books and impact campaigns that immediately followed Seasons of Life and Land included Yellowstone to Yukon: Freedom to Roam with Florian Schulz, The Last Polar Bear with Steven Kazlowski, and Salmon in the Trees with Amy Gulick. These projects brought places like the wildlife corridor from Wyoming to the Arctic, America’s Arctic, and the Tongass rainforest to life. Using books as a media platform, Braided River creates exhibits, presentations and media campaigns that reveal the beauty and ecological importance of these places, and encourages everyday citizens to take action to preserve natural treasures.

Today, and over two dozen books and projects later– Braided River works closely with a variety of educational and advocacy organizations to make sure that each project has a tangible impact, from preventing oil drilling in the American Arctic, to promoting sustainable fishing and forestry. By increasing public awareness of conservation issues, Braided River hopes plays a unique role in protecting America’s irreplaceable wild places and sacred Indigenous lands for generations to come.

Connecting people to wild places

Many people view wilderness as something that exists “way out there” apart from everyday life. Polls show that these same people would readily endorse protection of the natural world in large numbers if given a reason. By connecting the overall health of our planet to our own backyards and personal interests, Braided River makes environmental issues tangible. When someone learns that the birds at their backyard feeder may have traveled from breeding grounds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the tragedy of opening this land to oil drilling becomes palpable.

Braided River links issues back to home ground. We start with a subject of great environmental concern, and critical need for attention. We then create an emotional connection, clarify the issues, and define solutions.

We are continually learning from our work—building upon what connects with audiences, readers, and the media—while avoiding messages that fall flat, or don’t resonate.

20 years later and the fight is still on

This week we celebrate the 63rd anniversary of the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Almost every year since we began this work in 2003, legislation has been introduced to drill on the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and every time we have successfully kept drilling at bay. Without permanent protection, however, the fate of these lands will remain tenuous. This is why we continue the fight– with more books, more media, more outreach and an expanding network of Arctic protectors.

A brief political history of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

For over 60 years, citizens have called on the United States Congress to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northeast Alaska.

There is a long history of citizen engagement in its protection, starting with visionary conservationists Olaus and Margaret Murie in the 1950s, who led campaigns to establish the nation’s first ecosystem-scale conservation area. In 1960, Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower made this vision a reality by establishing the 8.9 million acre Arctic National Wildlife Range specifically for its “unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values.”

President Carter signing the Alaska National Interest Lands Act in 1980.

In 1980, under the leadership of Democratic President Jimmy Carter, Congress continued this legacy by expanding this pristine region, designating much of the land as protected Wilderness, and renaming it the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge under the Alaska National Interest Lands Act (ANILCA). At 19.6 million acres (the size of South Carolina), it is the largest national wildlife refuge in the United States. Combined with adjacent Ivvavik and Vuntut National Parks in Canada, the Arctic Refuge is part of one of the largest protected ecosystems in the world. However, due to political pressure during these negotiations, the 1.5 million acre coastal plain, the biological heart of the Refuge, was left unprotected. ANILCA prohibits oil and gas development on the coastal plain, but allows the opportunity for a future act of Congress to permit it. Since 1980 there has been relentless debate about the future of the 1.5-million-acre coastal plain.

The Arctic Refuge includes lowland tundra, freshwater wetlands, coastal marshes, mountains, and lagoons. More than 250 animal species rely on this intact wild Arctic ecosystem, including scores of migrating birds who rely on the food and abundant 24-hour light of summer to raise young before migrating thousands of miles to all fifty states, and six continents. The coastal plain supports hundreds of thousands of the migrating Porcupine caribou herd, rare musk oxen, wolves, grizzly bears, and wolverines; polar bear dens are found on the coastal plain. It has been home to two Indigenous peoples for many thousands of years—the Gwich’in Athabascans and Inupiats.

Starting in 1986, a bill to protect the Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain as Wilderness has been introduced in every Congress. However, efforts to open the Arctic Refuge to oil and gas drilling have been just as persistent. Due to avid public support for protecting the Arctic Refuge from drilling, these measures have failed.

Our goals are the same as they were in 1950: Congress and the Administration should take steps to secure the strongest protections possible for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

How Braided River works

We received a call from Dan, a self-described “Arctic Activist” of many years. He bought a dozen copies of our book Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Seasons of Life and Land, and told us the book was the best tool he had found to explain to his family and friends why he was so engaged in preserving this remarkable, distant, wild place.

While ordering more books, he mentioned that one of his oldest friends runs a gas station. When Dan gave his friend the book, the friend checked out the title, peered over the rim of his glasses and said “you have got to be kidding.”

Dan pleaded with him to just take a look, and the friend finally relented. “Because you are my buddy, I’ll do this for you.”

Days passed, and Dan asked, “Have you looked at the book yet?”

“No, I haven’t.”

Weeks passed, and Dan would occasionally check in. “Have you had a chance. . .”

“No, not yet,” the friend always answered.

One day the friend said: “OK, for you, I looked at your book. I know you care deeply about this. I looked at all the photographs, and even read some of the essays—as much as I could take of them, anyway. But you need to consider some important things about my life.

I am an oil man. I run a gas station. I feed my family on oil, and put my kids through school on oil. Oil is my life. I don’t believe the combustion engine is going away any time soon.” He paused for a moment, and continued: “But I want you to know: I do not want the oil under that land. I had no idea there was a place on this earth that was so beautiful.”

The significance of wilderness is sensed through beauty. Capture the heart, and the mind will follow.